Manuel Montero

El libro cuenta con un espléndido prólogo de Manuel Montero, escrito en castellano, euskera e inglés.

Manuel Montero (Bilbao, 1955) es catedrático de Historia Contemporánea, Universidad del País Vasco. Ha publicado diversas obras relacionadas con la historia económica y política del País Vasco, tales como Mineros, banqueros y navieros (1990) y La California del hierro. Las minas y la modernización económica y social de Vizcaya (1995). En ellos estudió la explotación minera y el proceso de industrialización que se produjo en la margen izquierda de la ría del Nervión. [Leer más]

In the beginning there was iron. The Romans told us that they were amazed to see «a whole mountain of iron» in Somorrostro. Pliny probably based these words on hearsay and must have exaggerated, but he was right in that there was a huge mass of ore. Later, many centuries later, more than one thousand years, this iron began to be exploited. It was melted in low furnaces and mixed with charcoal. And so ironworks were set up all over the Basque Country, above all in the coastal provinces. We know they already existed in the 13th Century. Since then iron has always melted in Basque furnaces. This has been one of the longest standing activities among us. And it has been decisive in creating us and forging our historic vicissitudes. It would be impossible to understand anything without iron.

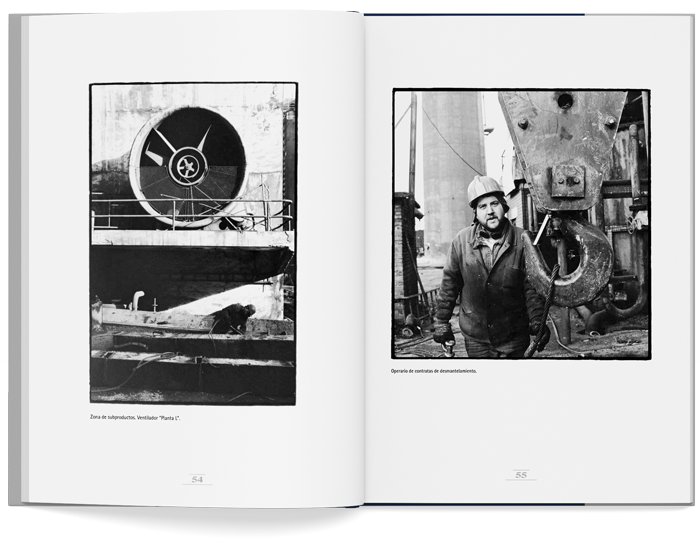

It is unusual. Iron hardly appears among the collective pictures with which the Basques are usually identified today. What we do see are peasants, fishermen, farmhouses, fishing boats, flocks of sheep, people strolling round the arcaded plazas of large cities, bulls pulling huge blocks of stone, groups of carnival goers dressed in animal skins sounding a kind of cow bell, farming tools, ever green fields, the sea breaking on the rocks. Never the mines or iron. Sometimes boats on the Bilbao estuary. At most a fleeting image of the blast furnaces at the time when they used to pour out their smoke on the left bank of the river. This is the closest we get to the iron, if we do not take into consideration the few historic evocations of blacksmiths. Never the miners, hardly ever the industrial suburbs. And the iron and steel workers only appear in public pictures which talk about dismantling factories. As if they were from another planet, another place, another time. As if they were an embarrassment.

It is unusual. This odd indifference towards the trades which have most characterized the Basque Country and have best represented it. It is unusual because nothing would be the same without the work of those who laboured in the mines over the centuries, without the daily toil of extracting the iron ore, cracking it and loading it onto the horses, carts pulled by oxen, the overhead tramways, onto the railways and carrying it down the winding tracks to the wharves, the ironworks or the modern iron and steel mills. Everything would be different without the workers who melted the iron ore in the furnaces, converted and laminated it.

Not only the left bank: over centuries the heart of the Basque economy has beaten to the rhythm of the iron extracted from the Triano mountain. The ironworks which grew along the rivers of Vizcaya and Guipuzcoa worked it and provided jobs for hundreds of men. There were also the men who transported the ore, woodcutters in the forests, men who prepared charcoal, others who carried the converted iron to the yards where it was sold. The history of the Basque Country could not be understood without mentioning iron. Without it, it would be impossible to explain that although agriculture was poor –foodstuff was imported even in the best harvest years because agricultural production did not cover their needs– the two coastal provinces were densely populated. Exporting refined iron, importing raw materials: both activities are at the economic heart of our history.

It is unusual. Iron hardly appears among the collective pictures with which the Basques are usually identified today.

Why then, does iron hardly ever figure nowadays in collective pictures? Why are the miners and metal workers of our left bank something of an embarrassment for the Basque Country, both historically and at present. This is not the right place to go into the reasons for such a peculiar phenomenon. It should be noted, however, that behind this lies the longing for an idyllic and harmonious past which never existed. There is also the fantasy of a present without conflicts or bitterness. They do not belong to the peaceful picture of the Basque Country which was willfully designed by our public figures.

We have to admit it: the worlds which were built upon iron do not reflect lyrical images. They do not fit in with present-day rural idealizations or the reluctance to include industrial modernity in the imaginary ideal Basque Country which is usually so successful. Mining areas make up one of the most exceptional landscapes of Vizcaya, few are so powerful. But, of course, they are not peaceful, nor suitable for tourists fleeing from desolation, and they are of no use for pretty postcards. Nor are the dark, threatening factories or the overcrowded towns and working class suburbs preferred by our politicians when they show illustrious visitors round. […]