In the beginning there was iron. The Romans told us that they were amazed to see «a whole mountain of iron» in Somorrostro. Pliny probably based these words on hearsay and must have exaggerated, but he was right in that there was a huge mass of ore. Later, many centuries later, more than one thousand years, this iron began to be exploited. It was melted in low furnaces and mixed with charcoal. And so ironworks were set up all over the Basque Country, above all in the coastal provinces. We know they already existed in the 13th Century. Since then iron has always melted in Basque furnaces. This has been one of the longest standing activities among us. And it has been decisive in creating us and forging our historic vicissitudes. It would be impossible to understand anything without iron.

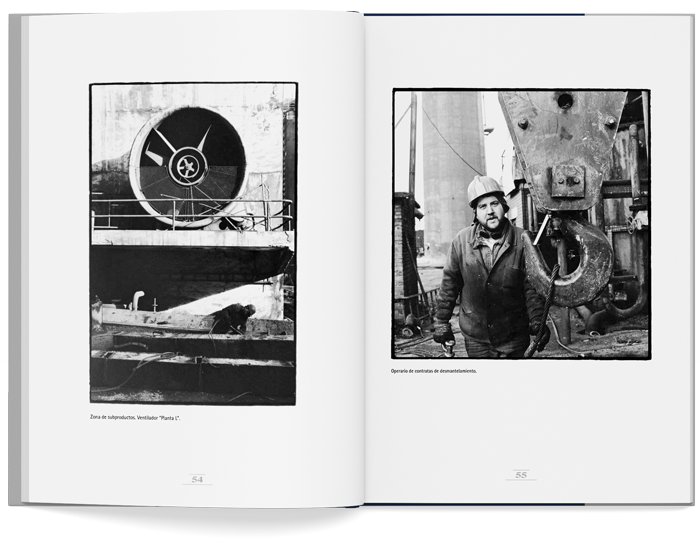

It is unusual. Iron hardly appears among the collective pictures with which the Basques are usually identified today. What we do see are peasants, fishermen, farmhouses, fishing boats, flocks of sheep, people strolling round the arcaded plazas of large cities, bulls pulling huge blocks of stone, groups of carnival goers dressed in animal skins sounding a kind of cow bell, farming tools, ever green fields, the sea breaking on the rocks. Never the mines or iron. Sometimes boats on the Bilbao estuary. At most a fleeting image of the blast furnaces at the time when they used to pour out their smoke on the left bank of the river. This is the closest we get to the iron, if we do not take into consideration the few historic evocations of blacksmiths. Never the miners, hardly ever the industrial suburbs. And the iron and steel workers only appear in public pictures which talk about dismantling factories. As if they were from another planet, another place, another time. As if they were an embarrassment.

It is unusual. This odd indifference towards the trades which have most characterized the Basque Country and have best represented it. It is unusual because nothing would be the same without the work of those who laboured in the mines over the centuries, without the daily toil of extracting the iron ore, cracking it and loading it onto the horses, carts pulled by oxen, the overhead tramways, onto the railways and carrying it down the winding tracks to the wharves, the ironworks or the modern iron and steel mills. Everything would be different without the workers who melted the iron ore in the furnaces, converted and laminated it.

Not only the left bank: over centuries the heart of the Basque economy has beaten to the rhythm of the iron extracted from the Triano mountain. The ironworks which grew along the rivers of Vizcaya and Guipuzcoa worked it and provided jobs for hundreds of men. There were also the men who transported the ore, woodcutters in the forests, men who prepared charcoal, others who carried the converted iron to the yards where it was sold. The history of the Basque Country could not be understood without mentioning iron. Without it, it would be impossible to explain that although agriculture was poor –foodstuff was imported even in the best harvest years because agricultural production did not cover their needs– the two coastal provinces were densely populated. Exporting refined iron, importing raw materials: both activities are at the economic heart of our history.

Why then, does iron hardly ever figure nowadays in collective pictures? Why are the miners and metal workers of our left bank something of an embarrassment for the Basque Country, both historically and at present. This is not the right place to go into the reasons for such a peculiar phenomenon. It should be noted, however, that behind this lies the longing for an idyllic and harmonious past which never existed. There is also the fantasy of a present without conflicts or bitterness. They do not belong to the peaceful picture of the Basque Country which was willfully designed by our public figures.

We have to admit it: the worlds which were built upon iron do not reflect lyrical images. They do not fit in with present-day rural idealizations or the reluctance to include industrial modernity in the imaginary ideal Basque Country which is usually so successful. Mining areas make up one of the most exceptional landscapes of Vizcaya, few are so powerful. But, of course, they are not peaceful, nor suitable for tourists fleeing from desolation, and they are of no use for pretty postcards. Nor are the dark, threatening factories or the overcrowded towns and working class suburbs preferred by our politicians when they show illustrious visitors round.

And these industrial trades –staring workers, groups of men in overalls– averse to poetic fantasies and populist indulgences, produce a certain unease among those who dedicate their lives to running ours, whatever party they may represent. They are disturbing. The reason is that they cause problems, and our politicians do not like this, probably because they are convinced of their ill luck in inheriting a conflictive society and that they would have shown their worth in a different society from ours, one which was made for the enjoyment of the authorities. But this is all there is.

What we have is the left bank, a world apart. The area where the Basque Country became modern: it is difficult to assess the historic debt which we owe to the mining and industrial areas which spread along this bank of the river Nervión. It is enormous. It was along the outskirts of the estuary that industrialization grew up. A traumatic process which did not only consist of building factories. It also meant building a new society and a new booming and prospering economy, whose influence soon spread beyond the reduced area of the factory installations. Everything changed and Bilbao, Vizcaya and the Basque Country underwent a process of modernization whose profile and pace was set by the blast furnaces.

For a century and a half –from the mid 19th century until twenty years ago– one of the signs of identity of the Basque Country was its capacity to grow, to take in people arriving from other lands. Every ten years the census showed net increases in population, an incomparable phenomenon elsewhere due to its continuity and intensity; uninterrupted until 1990, the balance was always greater than the preceding decade. This constant flow, nourished by iron, has developed the varied and plural character of our society, its singular, undeniable feature.

«Mount Somorrostro, which provides the ironworks of the Basque Country with most of their iron ore, is situated three leagues to the west of Bilbao and half a league to the south east of the town of San Juan de Somorrostro in the Encartaciones of the domain of Vizcaya. This mountain, though quite high, has a gentle slope, and is not very uncomfortable in summer, but in winter it is extremely muddy due to the continual rain which makes traffic impossible or at least very dangerous and exposed.» With these words, Fausto Elhuyar described the main mining area in Vizcaya in 1783. One hundred years later, the Somorrostro iron which had supplied the raw material to the ironworks of the Basque Country fulfilled other economic functions, just as decisive as those it had performed during the Old Regime. Many of the problems that mining had presented, as explained by Elhuyar, had disappeared. They were removed in the mid 19th Century, the beginning of the systematic exploitation of Vizcayan deposits, when the raw material began to be supplied to English blast furnaces.

It was the invention of the Bessemer process for making steel in 1855 which was the main reason for the interest of British industry in the mines of Vizcaya. Bessemer needed a certain kind of ore, the non phosphoric iron which was plentiful in the Vizcayan mines, in ideal conditions for its mining and exportation to Great Britain: it was a rich ore, located close to the coast, in an area which, from an English point of view, abounded in cheap labour. And so, in the 1860s, the mining area of Vizcaya began to get organized with the aim to supply, firstly, the English metal industry and, secondly, the French, Belgian and German industries.

The decision to extract Vizcayan iron to supply the modern metal industry is, as such, one of the most decisive events in the historical evolution of Vizcaya and the whole of the Basque Country. It became the main undertaking of the economy. Approximately 85 million tons of iron were shipped abroad from the docks of the Nervión before the end of the century.

In order to do so, it was necessary to transform the geographic and human landscape of the area. Railway lines had to be laid to link the mines with the port which, in turn, had to adapt to the new level of traffic. Mining installations had to be built: furnaces, overhead tramways, washhouses… In addition, a new workforce, par tly immigrant, would rapidly change the social and demographic make-up of the left bank of the river: the growth of several towns and the emergence of a new working class closely linked to mining are some of the phenomena which explain certain key aspects of our history.

But the consequences of the iron ore industry were not limited to those produced by the huge mining industry, spectacular as they were. The sale of iron generated a flow of capital which enabled Vizcaya to fully enter into the world of industrial capitalism. Investment in the local metal industry, shipbuilding, banking, hydroelectric industry… would contribute far more than any other phenomenon towards the conversion of Vizcaya in an industrial region. Our development moved, throughout many decades, to the rhythm marked by the departure of ships loaded with ore: to a certain extent, this was its root, its raison d’être. The wealth created through the sale of iron ore was not, therefore, short-lived. It established roots and flourished in a new society to which it supplied funds and capital. The Vizcayan economy, which had already received a decisive push, was able to continue its modern development, even after the iron ore began to get scarce.

Specialization in the iron and steel industry on the left bank of the Nervión began in 1855. 140 years ago the seed was sewn for what through time would grow to be Altos Hornos de Vizcaya. It is interesting to note the atmosphere which reigned at the 35 time this decision was taken and led to our modern industrial development. The ironworks were beginning to be abandoned because they could no longer compete with the blast furnaces of the British industrial revolution. A fundamental element of the traditional economy of the Basque Country was disappearing. «It is the ruin of our land», «it is destroying our way of life»: the newspaper commentaries of the time are full of laments. An era had come to an end and it was feared that it would mean the definitive collapse. It was not. From 1841 on, some old ironworks began to install new modern machinery. They still used charcoal, but they foretold that not all was over for the iron industry in the Basque Country. To the contrary. As the years passed new techniques were imported, techniques which had been successful in Europe. In this climate of events the first iron and steel factory was installed on of the left bank of the Nervión.

It was backed by the Ybarra Brothers and company. This was a family of miners and traders who, from years before, had run a small metallurgic business in Guriezo (Cantabria), called ‘Nuestra Señora de la Merced’. As this location made it difficult to obtain iron and distribute their products, they decided to build a new factory on the estuary, at the confluence between the rivers Galindo and Nervión. The bought the land known as ‘El Desierto’, a paradisal area at that time, if we are to believe the inspired verses of Samaniego, who 50 years earlier had taken refuge at a Carmelite convent there when escaping from the Inquisition.

And so the ‘Nuestra Señora del Carmen’ factory was set up. The decision was transcendental. This led to the changes in the left bank and the specialization of the iron and steel industry. El Carmen was the first factory in the Basque Country which used charcoal, at first in low furnaces. Around the year 1872 the first blast furnace to burn coke was built. This work was interrupted during the Carlist Wars which ended in 1876. And, in the postwar, despite the tragic destruction caused by the war, at a time when the country was in the grip of a new pessimism, the most surprising event of our contemporary history took place. A sudden economic boom occurred. Thousands of workers came to work in the mines of Vizcaya. Approximately three thousand steamships set sail from the Nervión each year loaded with iron and headed for the ports of northern Europe. Companies with exotic names, a local name and a foreign surname, settled in Vizcaya: Franco Belge des mines de Somorrostro, Orconera Iron Ore Co. Ltd, Luchana Mining, Triano Ore Co. Ltd, Bilbao River and Cantabrian Railway, Parcocha Iron Ore… Iron mining created a new working class, subject to appalling living conditions and, at the same time, some families grew rich. The investment of huge profits led to the definitive industrial boom.

In 1878 a new ironworks, the San Francisco factory, was built. In 1882 it was the turn of the Vizcaya factory blast furnaces. They were situated on the beach called Sestao, on wetlands which the estuary formed downriver from the Galindo. It was also in 1882 that El Carmen was converted into Altos Hornos de Bilbao, to equip it with large scale installations. And so, these three metalworks became the biggest and most important factories ever built in the Basque Country. They had the capacity to give an important boost to industrial development. Before the end of the century, several metallurgic factories (La Basconia, la Iberia, Aurrerá…) were bunched together around the big factories. Later, in 1901, the merger of Altos Hornos de Bilbao with La Iberia led to the setting up of Altos Hornos de Vizcaya. This industrial group was joined some years later by the San Francisco company.

By this time the river had acquired its present appearance. The river, as we know it,Vis a human creation. It was essential to adapt the course of the Nervión to the new needs. Its original characteristics were not suitable for the heavy traffic which was to come; the average load of cargo ships was less than 500mt at that time, quite a small volume when compared to the trade forecast for the future. In a surprisingly short period of time, over the last two decades of the 19th century, what was to be the greatest collective effort ever was made to transform the physical space of the Basque Country. It is interesting to think of the Nervión at the end of the 19th century. New large scale blast furnaces were being built on the left bank. Numerous ships sailed up the river each day towards the loading docks by the mines. On average, about twenty ships crossed the bar daily, waiting for high tide. Some headed for the docks near to Bilbao, along the difficult provisional canals which were opened in the riverbed. And, in this colourful panorama, mud lighters, steamships, barges, cranes and dredgers rallied round to reconstruct different parts of the river.

Industrial prosperity, centred on the conversion of iron, had begun to take effect in Vizcaya. It was not optimism all round, however. There were the precarious living conditions of the workers, which only improved after an intense series of struggles. There was urban overcrowding, following the rapid expansion of industrial towns which grew progressively and without interruption over decades. There were also the successive crises which typified the cycles of the iron and steel industry. And, finally, there was the pessimism of those who imagined that industrial development lacked a solid base and was due to a kind of historic accident which had favoured the value of Vizcayan iron, and that it would all come to an end when the iron ore ran out.

This kind of skepticism is well expressed by the writer Vicente Blasco Ibañez who, in his novel ‘El Intruso’, depicts the first moment of splendour of the river and predicts its abrupt end:

«Fortune had passed one moment over this land, as it does over other lands, without leaving anything solid. Bilbao sometimes had the appearance of the historic cities of Italy, which were once great, filling the world with the power of their trade, and today are melancholic cemeteries of a glorious past. The palaces of the Ensanche are left standing, the river is prodigious with its port which seems to await the squadrons of the whole world. But the palaces are deserted; the Abra, with its few ships will have the sad grandness of an immense cage with no birds, and the foundries, the steel mills and the loading docks, will be ruins with their broken chimneys, reminiscent of those solitary stacks which make the solitude of the dead metropolis even sadder.»

These words seem prophetic and describe these times of dismantling industry, when the «foundries, the steel mills, the loading docks» look like «ruins with their broken chimneys». However, despite the indubitable attraction of these words of almost a hundred years of age, the prediction was mistaken. Fortunately, Blasco Ibañez was wrong to suppose that industrial development was a passing phase and that it would vanish when the spring of Vizcayan iron ore ran dry. From 1899 on, the year when six and a half million tons of ore were extracted, the volume of iron which was produced began to descend.

The economy did not collapse as a result, because the investment of mining profits had already generated a new productive base capable of holding its own, maintaining the development. The number of miners gradually decreased, but the new factories, shipyards, iron and steel works were already creating employment. «A generous and abundant numen protected the city. He dreamt of the destiny of the chosen people: live an enjoyable and easy life. Wonderland? Bilbao was Wonderland» was Julián Zuazagoitia’s portrayal of the industrial prosperity of the years of the First World War, another golden era of the Vizcayan economy. «The estuary is one of the most stimulating things in Spain. I do not believe there is anything on the peninsula which gives such an impression of power, toil and energy as these fourteen or fifteen kilometers of waterways»: said Pío Baroja, some decades later, confirming that, contrary to beliefs at the turn of the century, the economy created by iron was well rooted and had capacity to survive beyond the end of the splendour of the mining era.

There were a series of economic cycles. The recession at the turn of the century was followed by the euphoria of the time of the First World War and subsequent difficulties gave way to the roaring twenties, the economic slump of the thirties, the autocratic anguish of the postwar period, slow economic recovery and, finally, the elated development of the seventies – when the industrial zones became congested and Vizcayan companies set up their factories upriver from Bilbao. Since then installations on the banks of the Nervión have been dismantled, restructured, classified as obsolete or belonging to an aging society in the need of reconstruction.

And, between impatience and pessimism, it sometimes seems that the end of the story is near, that the river of iron has fulfilled its mission and that two thousand years after it made its entry into the history books, it has changed into a burning match which cowardly politicians and parties pass from one to another, afraid of burning their fingers, wishing they had lived in other times or another world. But there is no other time or other world. And nothing has ever been easy. Iron was the seed to industrial prosperity, but it was sewn by man, through collective effort. For that reason there is always room for hope. The blast furnaces of this century are disappearing, but the society which was created by iron still remains throughout time, a world which has overcome successive structural crises and which, prophets of doom apart, has always demonstrated its collective energy.

It is the story portrayed by Fidel Raso in the pages of this book. The end of an era and the beginning of another. Not the inauguration of the dead metropolis which Blasco Ibañez announced, but the last billow of smoke from the blast furnaces of Altos Hornos and, also, the construction of the new steelworks. The past which fades away and the oncoming future. But the changes of the cycle are dramatic, full of uncertainties. Hence the resounding silence of the pictures of the last stream of molten iron in the history of the Vizcayan iron and steel industry, a desolate farewell to the past 140 years, almost a century and a half of molten iron in the same places along the left bank of the Nervión. It is the end of a continuous river of thousands and thousands of tons of iron which has flown for what seemed like never-ending decades. It all ends here. Fidel Raso’s photographs capture this moment. We are moved by the solemn and solitary look on the faces of the workers who are watching it all come to an end. Without ceremonies or the authorities who dislike presiding over concluding events. They are tense pictures which show a surprising air of everydayness, an act repeated hundreds of times: the knowledge of the fact that the operation will never be repeated does not alter their routine appearance. Great historic events are sometimes symbolized by an everyday act, a trivial experience. This is one of those moments.

These photographs also portray the unnoticed farewell to the smoke from the ironworks which characterized the landscape of the river for so many years. The dismantling of the factory structures which our economy has long depended upon. With no other witnesses than a photographer. But there is still more: there are the pictures, sometimes sordid and always surprising, of an aging, too old factory. We can see the precarious conditions of some of the installations. And the photographs themselves explain why the end has come to Altos Hornos de Vizcaya. They do so more rigourously than any of the arduous economic studies which analyse the technological backwater and whose pages are filled with the terms ‘critical’ and ‘cacophonous’, usually used to explain these things: obsolete, obsoleteness. How this has come about is the subject of that brilliant photograph of the worker oiling the railway lines which will never be run along again by a train. No one had remembered to tell him that this daily task was no longer necessary. They were not even capable of organizing a sensible ending.

But there is also the inauguration of the construction of the new steelworks, the large group of politicians whose number contrasts with the few workers who were left to close a chapter in the history of Vizcaya. The inaugurators are bunched together, in curious expectation, they seem to feel cold. It is a sign of the times, starting undertakings with an uncertain future. There are no workers at the inauguration, they are not in the photograph. Only the politicians and the drivers of their official cars, calmly waiting for them. They are the customs of this era with its sights on the future.

But this book also takes in the future, those beautiful pictures of the birth and growth of the steelworks. Here the pictures seem like engravings from the past century when everything seemed possible and our world was beginning to be built. Behind all those beams are the towns which erected the blast furnaces. Fidel Raso also portrays 40 the surroundings of the factories and one can sense the overcrowding and the resignation in the face of the end of an era, the incomprehensible tides in which our economy is constructed, destroyed and reconstructed and which, finally, determine our lives. This kind of metaphysical force is beyond the control of the individual, who is unable to even understand it. But, after all, there are reasons to believe in the future. It is uncertain, of course, but what future has not been?

The seed of iron flourished in critical hours: the beginning of the 19th century when the traditional ore trade began to collapse and everything seemed to break up for good; the end of the Carlist Wars, in a dark and divided country which was classified as bereft of hope; the successive crises which struck our industrial history over this century; the anguish of the post war years, full of hunger and shortages. And now, the crisis which we have to live, captured in the work of Fidel Raso. Iron, the factories, they have always been a collective task, and that is why there is no room for resignation. It is true that nothing will be the same again, that the end of an era lends itself to nostalgia. But, at the end of the day, we have a human element which has rebuilt its present so many times, overcoming the ominous and pessimistic forecasts. It is the task which we have to undertake, and beyond the depressive economies and structural breakdowns, that kind of supernatural force, remains the social energy which was sewn by iron. We have overcome worse difficulties.

Fidel Raso is right. Everything starts with iron. Only memories are left of the mines, those clefts in the earth with which this book opens. There were mines and miners, and then they disappeared and we were left with the factories. Now our iron and steel history is also departing and the new steelworks of the future begins to take shape. Another era. For this reason this book portrays a historic, decisive, transcendental moment. The moment we are living. We should reflect upon it. But he also portrays the past and a glimpse of the future. And he traces the tracks of human effort, collective hopes. The seeds of iron.

Manuel Montero

English Translation: Kenny Mc Donnell